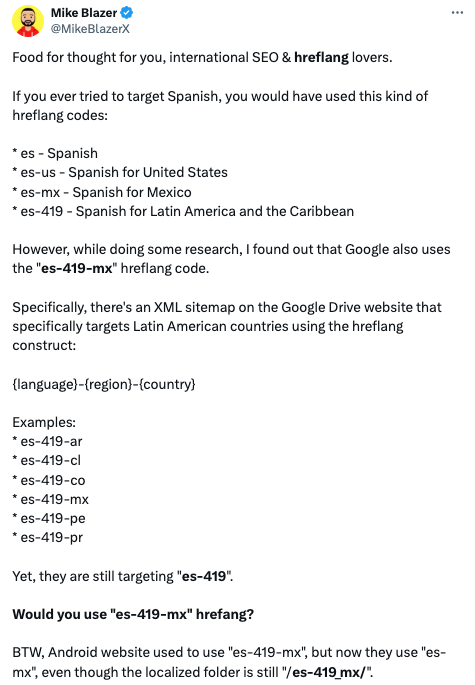

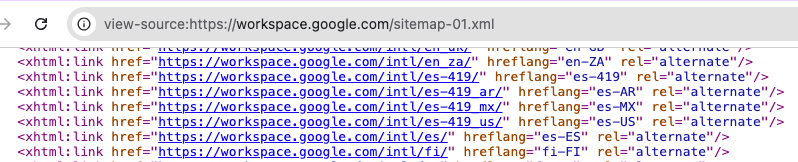

In a post on X, Mike Blazer asked the recurring question about using es-419 and a few adapted variations of it, showing an example of the hreflang XML sitemap for Google Drive that extended the es-419 further, appending country codes to the end.

Ironically, using the further extended es-419 code was the least of their concerns with this hreflang implementation. Scroll to the end for the other and bigger problem with the implementation.

This prompted Gianluca Fiorelli to respond on X, indicating that Google has confirmed this is not a valid language and region string, which necessitated a response to Gianluca’s post referencing a brilliant 5-year-old article by Dan Taylor, which indicated that es–419 is correct. While one of the most knowledgeable International SEO and Hreflang Experts, unfortunately, Dan Taylor does not work for Google, thus this is not a definitive answer.

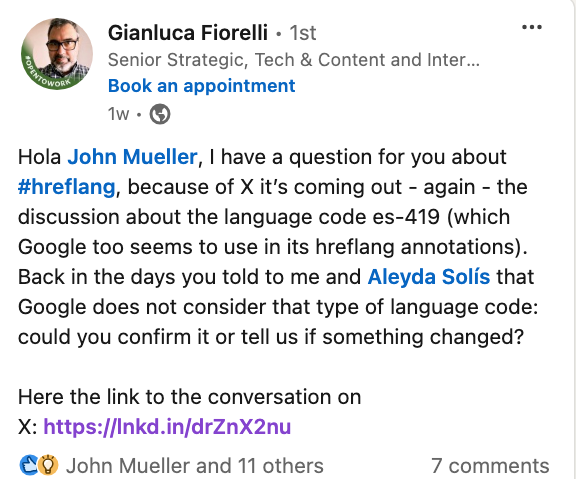

Gianluca Fiorelli again asked Google for clarification on whether this is acceptable. I suggest asking again because various Google representatives have addressed this question multiple times on social media and at conferences.

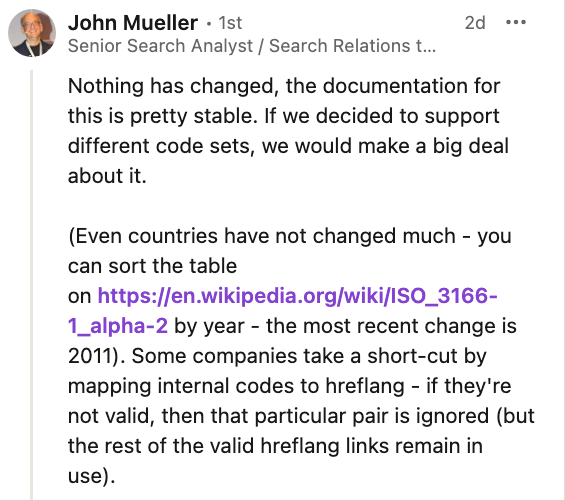

John Mueller responded that the documentation had remained the same and that if they had made a change, they would notify people.

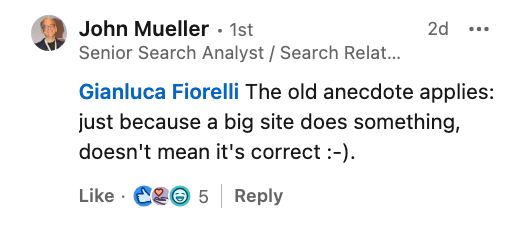

John further stated that you should not follow what big companies do. This is also a case of do as we say not as we do.

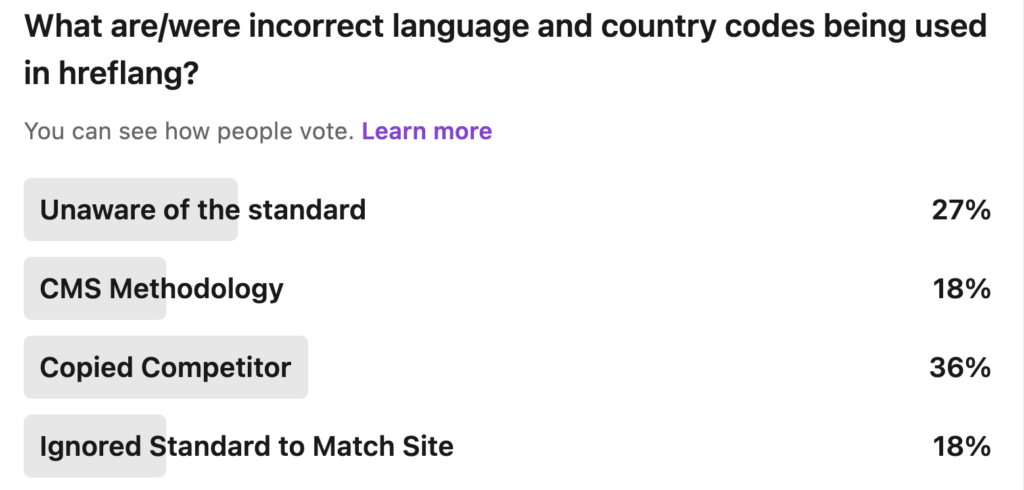

John further stated that you should not follow what big companies do. Interestingly, my survey from earlier this year on why companies use incorrect hreflang codes revealed that 36% of companies with errors copied the implementation of a larger competitor. I am also tempted to classify this response as a “Do as we say, not as we do,” but I will elaborate on that in a moment.

I rant at conferences and multiple times in my 2.5-hour hreflang errors course that Google fosters ambiguity when they respond with “it’s in the standards” or “the standard is clear,” rather than providing a definitive yes or no. This allows many to interpret this lack of a definite no as a maybe and will often give examples of where there might be an exception. In my training, there are multiple examples of where a clarification opportunity was missed, further resulting the perpetuation of the deviation from standards.

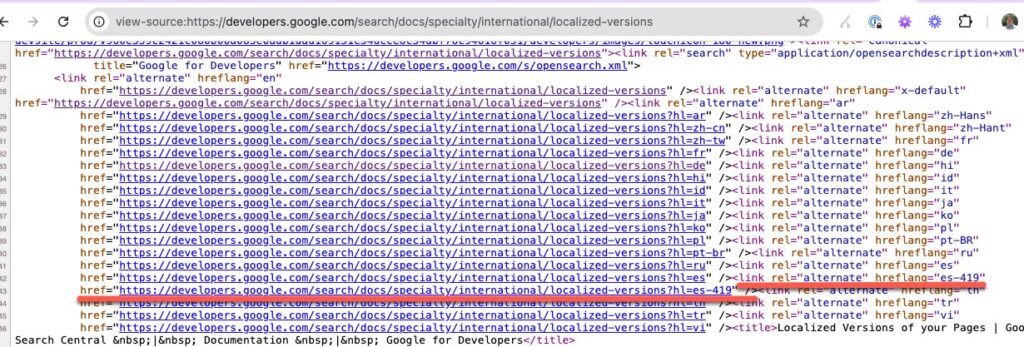

In the case of es-419, whenever I parrot the party line that es-419 is not part of the standards, I always get shown the hreflang tags from the very page stating they are not allowed. https://developers.google.com/search/docs/specialty/international/localized-versions#language-codes

It is one thing to find it used on other parts of Google, as in the case of the Google Drive and Android site, where you can say they are like every other dysfunctional and non-collaborating dev team, where they do what they want, enable-based on CMS rules, copy a competitor or use whatever blog post suits their needs. However, when it is on the page with the standard maintained by the team that wrote the standards and insists the standard is clear, it is hard to argue that it is not a valid element.

Hreflang Syntax and Standards

The hreflang element was initially introduced by W3C to help browsers move between and process different languages more efficiently. A few years later, it was expanded to the link element to enable search engines to understand better the language of the content they were indexing. Google adopted and promoted this function to allow multilingual websites to designate both the language and the region to prevent those pages from being considered duplicates.

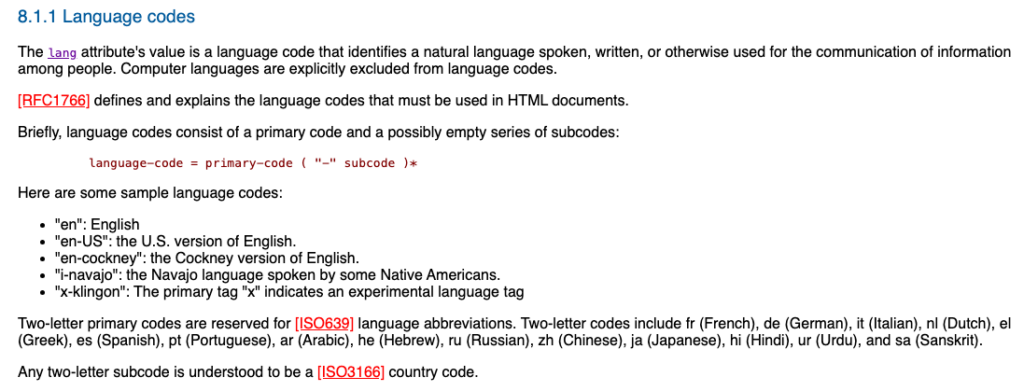

Both the W3C https://www.w3.org/TR/html401/struct/dirlang.html#h-8.1.1, (the higher-level standard) and Google (https://developers.google.com/search/docs/specialty/international/localized-versions) indicate that language is the primary code, but you may also add a secondary subcode to designate the country/region. It is often this subcode where the interpretations differ by developers and SEOs.

W3C – requires a primary two-letter code from ISO-639 and ISO-3166 to designate the country for the language. Note just before the ISO3166 reference that any two-letter subcode is “understood to be an ISO-3166 country code. This two-letter code statement clarifies that they mean ISO 3166-1 Alpha 2, a list of two-letter country codes.

Google similarly requires a language code specifically from ISO-698-1 (two-letter) and an optional second code for a region (country) ISO 3166-1 Alpha 2. This effectively makes the standard the same.

Deviating From the Standards

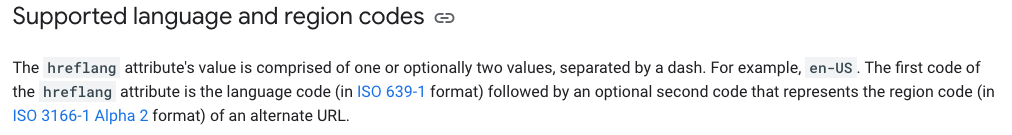

In my March survey of those who had incorrect hreflang codes, the majority, 36%, indicated that they had copied a competitor, exactly what John suggested they not do.

Where does the es-419 code come from?

The es is from ISO 639-1, the language code for Spanish, and the 419 code is from UN M.49 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UN_M49 a set of three-digit codes developed by the United Nations for statistical analysis.

In 2006, the International Engineering Task Force (IETF)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IETF_language_tag extended their documentation for international software development from simply ISO-639 and ISO-3166 to allow subtags of three to eight letters. This set the foundation for them to extend their guidelines to allow ISO 15924 four-letter script codes, UN M.49 three-digit geographical region codes, ISO 639-3 and 639-5, which cover nearly all languages.

Because this is the internationalization standard learned by formally trained software developers, it has entered content management systems and, most recently, in-house-developed hreflang implementations.

While it is a perfectly valid programming and internationalization standard, Google does not currently support it for hreflang. Many have asked for an extension of both the language and country standards for languages that are not in the two approved standards, as well as accommodating regional websites where some of the most frequent errors occur.

This helps me better understand the results of the “Why are your hreflang country codes incorrect?” survey I conducted in March. It does sort of answer why 36% of developers are willing to copy code from a large competitor, where they may assume they have highly experienced developers, and the 27% do not read or follow the Google or W3C standard, as their programming standards allow the code set.

Why does Google use it?

The knowledge of a parallel standard may explain why the Android team uses it on their website, as they reference it in the Android Developer Guide and Google Play Localization Guides. I can only guess that these developers are aware of the IETF standards and have used them, but are unaware of the W3C or Google hreflang standard. The original Google Drive hreflang XML sitemap, as shown in the screenshot (hint), was created using the URL path to generate the tags, as that is how the internal CMS was structured.

The Google Search Central team may have the same problems as every other dysfunctional and non-collaborating dev team when implementing hreflang. Prioritizing tickets to change it is impossible, as it is based on hardwired CMS rules. However, it is hard to argue that it is not valid when it is on the page with the standard maintained by the team that keeps the standards.

Google Drive’s Bigger Issue

It was surprising that no one mentioned the more significant mistake being made. In the screen capture of their hreflang XML sitemap https://www.google.com/drive/sitemap.xml it shows the hreflang alternate websites as https://www.google.com/drive/ but if you visit any of them, you are 302 redirected to the referenced URL on https://workspace.google.com/. This effectively breaks the hreflang for this website. Interestingly, they are using a 302 temporary redirect on what appears to be a permanent product rebranding. I just wrote an article on why Hreflang is critical during migrations and re-platforming due to the number of websites making this mistake.

Reviewing the hreflang XML sitemaps on the Workplace domain, they still use the same URL path with an es-419 code and an appended country code to designate the unique websites. Still, they have modified the hreflang element of those specific market websites to the correct language and country codes and use es-419 exclusively for the Latin America region.

To be a stickler for details, the US would not be part of the es-419 block as the US is part of North America, a different region code.

Does using es-419 Work?

I have seen both cases where this designation has been effective and those where it has not. When it has not, it was typically due to using hreflang tags on the page, and those pages had not been indexed. In the case of Google Workspace, although I did not check all fifty-two 419 markets, I did verify multiple locations across the region using a VPN and Incognito mode. In every case, the correct regional website appeared in the local market search results.