Why platforms, governments, companies, and consumers must share the burden of trust

This article was sparked by a Washington Post story last Friday about a traveler who was scammed after calling a fake number surfaced by Google’s AI Overview. Reading it, I realized the frustrations I first wrote about two years ago—when I questioned whether we needed “authenticated answers” for high-risk queries like visas, forms, and customer service numbers—have only gotten worse in the AI era. What follows is an updated reflection on where responsibility lies, and why we can no longer rely on “the first answer” to be the right one.

The New Danger of “Just Google It”

For more than two decades, we’ve trained people to “Google it” and trust whatever came first. That reflex worked—well enough—when search mostly served up a ranked list of links where authority could be judged by domain, branding, or reputation.

But now we’ve entered a new era. AI engines like Google’s AI Overviews, ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity don’t just return results; they give answers. Short, confident, neatly formatted answers that look official—even when they’re not.

And that confidence is fueling a wave of real-world scams.

A recent Washington Post story highlighted one traveler who asked Google’s AI Overview how to add activities to their cruise. The AI confidently displayed a customer service number. The traveler called it, paid fees, and handed over personal data—only to later discover it was a scammer’s line.

That’s not a fluke. It’s a pattern, and it’s spreading.

When Plausible Becomes Dangerous

This isn’t about obscure misinformation lurking in the dark corners of the web. These scams are front and center—in the top box of a search, in a bolded AI answer, in a paid ad above the official result. They thrive in situations where:

- The answer seems simple (a phone number, a form, a yes/no visa requirement).

- The information is fragmented (different rules for different nationalities, states, or agencies).

- Trust signals are buried or absent (official sites look unofficial, while scams look polished).

- There’s an opportunity to make money (fees, services, rebooking scams).

And they appear exactly when people are most vulnerable: stressed in an airport, booking travel, filling out government forms, or desperately trying to reach a customer service line.

Real-World Failures of Trust

- Visa Guidance Gone Wrong

An Australian traveler asked ChatGPT if he needed a visa for Chile. The answer? “No.” He showed up at the airport, only to be denied boarding. He needed a visa, which had to be secured in advance. Google’s results weren’t much better—surfacing “no visa needed” guidance intended for U.S. citizens. Correct data, wrong context, costly consequences. - UK Immigration ETA Vendors

When the UK launched its Electronic Travel Authorization system, commercial vendors immediately spun up lookalike websites. They performed the real service, but charged unnecessary fees. Their sites looked official, complete with logos. Disclaimers? Tiny. Many even advertised above the government’s own listing. - Airline Phone Number Scams

Fraudulent customer service numbers surfaced by search engines or AI summaries have led to travelers handing money to scammers to rebook flights. This isn’t new, and Google has long struggled with phone number spoofing, but AI’s bold, authoritative formatting makes the fake number look validated. I know multiple company owners who have told me about their panicked employees who were targeted during delays or missed connections. People searching for an “Airlines’ Customer Service Number” are often shown fake numbers, which are bolded in AI answers or paid ads. - Official Government Forms

- Even outside travel, we often need official government forms. For example, the IRS offers free EINs (Employer Identification Numbers)online for US business owners, which take just a few minutes to complete. But countless services charge to do it for you often because their pages are more user-friendly, rank higher, and feel more “official” than the actual IRS website.

- Official Government Forms

Even outside travel, we often need official government forms. For example, the IRS offers free EINs (Employer Identification Numbers)online for US business owners, which take just a few minutes to complete. But countless services charge to do it for you often because their pages are more user-friendly, rank higher, and feel more “official” than the actual IRS website. It has gotten so bad that the IRS, FTC, and many state governments have been doing PSAs and other announcements about the problem. Despite announcing and clarifying the marketing rules and taking action against the more egregious abusers, the search results are still littered with services that cross the line. This should be a pretty easy problem for Google to solve using AI.

Official Sites That Don’t Look Official

A few years ago, while planning a multi-country trip, I started researching visa requirements only to realize how unreliable and confusing the experience could be. In many cases, the official government site didn’t appear in the top results at all. And when it did, it often looked sketchy: outdated design, no security certificate, or hosted on a generic .com domain instead of something more authoritative like .gov.

To make matters worse, the official pages were sometimes littered with ads or vague boilerplate descriptions that did not indicate official status. In some instances, I later found out that these were authorized third-party vendors appointed by the governments themselves.

When Ads Undermine Trust

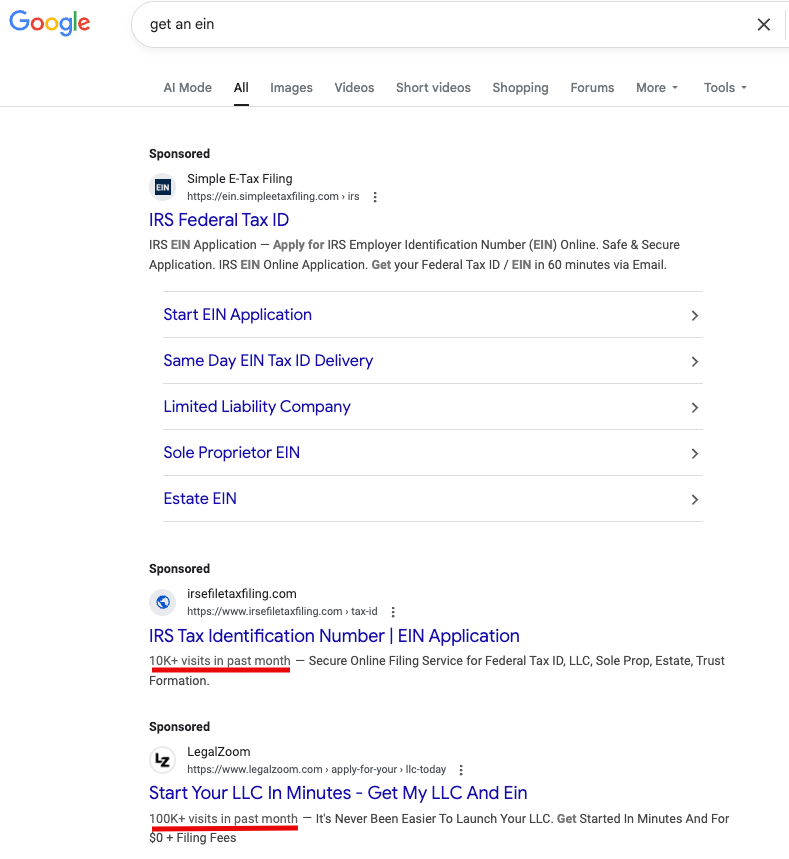

Search for “get an EIN” and you’ll see the contrast. In the organic results, Google surfaces the IRS site four out of five times. It’s precisely what you’d expect: the authoritative source elevated above noise.

But above those organic links sit three paid ads. One in particular looks almost indistinguishable from an official listing — multiple sitelinks stating the different needs for an EIN, government-style language, and the other two have visitor statistics in the copy: “10,000 visitors last month” or “100,000 visitors.” On the surface, those numbers sound like social proof. Subliminally, they validate legitimacy.

These companies aren’t scams as the FTC has stated — they’ll get you the EIN you need. But they’re charging hard-earned dollars for a process the IRS provides for free in minutes. And because Google allows these ads to run, they sit above the official source, siphoning money from confused or rushed users.

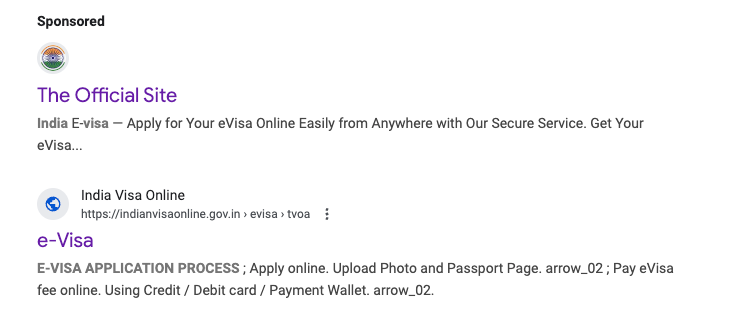

The same dynamic appears in other high-value categories like visas. While searching for an Indian tourist visa, I came across an ad that claimed to be “the official site.” Not an official site, but the official site — a subtle but powerful choice of wording that could easily make a searcher believe they’d reached the real government portal. This almost certainly slipped through Google’s automated ad review, where no human ever asked whether the phrasing might be misleading.

Meanwhile, the first organic result wasn’t much better: the snippet was a string of words scraped from the page, including step-by-step instructions with arrow characters that rendered as gibberish. Instead of signaling authority, it looked like nonsense.

This isn’t a technical challenge for Google. They already rank the IRS first in organic. The issue is economic: paid ads are too profitable to turn off. The companies buying them are succeeding — otherwise, they wouldn’t keep spending.

Which makes the uncomfortable truth clear: in cases where the authoritative source is unambiguous, the problem isn’t that Google “can’t” fix it. It’s that they won’t.

Who Bears Responsibility?

This is the crux: who should be responsible when the system misleads people?

- Platforms (Google, OpenAI, Meta, etc.)

- If you bold it, you own it. Presenting unverified contact information in a confident, formatted answer is reckless.

- They need provenance frameworks for high-risk data: phone numbers, visa requirements, government forms, and financial rules.

- At minimum: disclaimers, validation checks, and clear labeling when data is unverified.

- Governments

- Too many official sites are outdated, fragmented, or buried.

- They must modernize their digital presence, publish structured data feeds, and mark verified information.

- If a commercial vendor outranks an embassy for visa requirements, that’s not just a search problem—it’s a governance problem.

- Companies

- Many brands resist publishing clear contact details because they don’t want calls. But the vacuum gets filled by scammers.

- Firms must monitor how their brand shows up in AI engines, maintain structured data for support and policy pages, and protect users from impersonators.

- Letting scams dominate isn’t cost-saving; it’s reputational and legal risk.

- Consumers

- We can’t keep outsourcing all judgment.

- Stop trusting the first bolded answer. Verify. Use official apps for travel and banking—question whether a fee-based service is necessary for something that might be free.

- This isn’t victim-blaming; it’s survival in a new information ecosystem.

What Could Exist: The TRITS Concept

While wrestling with the frustrations of that multi-country visa exercise, I started sketching a prototype I called TRITS—Travel Requirements Information and Trust System.

The idea was simple in concept, hard in execution:

- Governments publish visa and entry requirements in a standardized, structured feed (like a schema for travel).

- Each record is authenticated at the source, with provenance logs.

- Airlines, booking sites, search engines, and AI models can consume the verified feed via APIs.

- End result: users always see authenticated, real-time requirements for their nationality, travel type, and transport mode.

The technical lift would be trivial compared to the trust gap it could solve. But the hard questions remain:

- Who funds it? Governments, airlines, or a shared trust consortium?

- Who maintains it? Immigration authorities? A standards body?

- Who’s liable if it’s wrong?

I shelved the idea because the incentives weren’t there—governments were slow to modernize, and commercial data brokers profit from confusion.

But the point is: this kind of system could exist. We already have provenance efforts like C2PA for media authenticity. Why not for travel requirements and safety-critical public data?

The Hard Truth: Shared Burden, Fragile Trust

The uncomfortable reality is this: no one party can fix this alone. Platforms can’t catch every scam. Governments can’t modernize fast enough. Companies won’t always prioritize user protection. And consumers, trained to value speed, rarely slow down to double-check.

This is why the ecosystem of trust is breaking. AI isn’t the villain—it’s the amplifier. It makes bad information look official, strips away context, and delivers it with unearned confidence.

We need a shared model of responsibility. Platforms must verify, governments must publish, companies must protect, and consumers must adapt. If one side shirks, the system fails.

Closing Thought

We’ve entered a moment where well-meaning tools are betraying well-meaning people. The danger isn’t just bad answers—it’s that those answers look official.

The AI era has exposed the fragility of our trust ecosystem. If we don’t rethink responsibility across platforms, governments, companies, and consumers, then “scammed by the answer” will become the default headline of this decade.

It’s time to build authenticated answers because convenience without verification is just another word for risk.

Footnote: Visitor numbers shown in ads (“10,000 visitors,” “100,000 visitors”) are often pulled from tools like SimilarWeb or internal analytics. They aren’t measures of trustworthiness—just traffic estimates repurposed as subliminal social proof.